On today’s Cow-Calf Corner, Mike Trammell, Oklahoma State University Southeast Regional Forage Agronomist, talks about legumes in grass-based grazing systems. Cow Calf Corner is the weekly series known as the “Cow Calf Corner,” published electronically by Dr. Derrell Peel, Mark Johnson, and Paul Beck.

There are several important benefits associated with establishing other forage crops into existing sods. Over the years, research and on-farm experience have shown that the addition of legumes to grass-based grazing systems can result in a number of potential improvements such as diversity, stand productivity, improved forage quality and extended grazing season. Legumes and grasses have unique herbage and root morphology traits that allow for a greater combined use of environmental resources such as light, moisture and minerals. One of the more compelling reasons to use pasture mixtures containing both legumes and grasses is nitrogen (N) fixation.

Nitrogen is required for high levels of forage production and N deficiency is a common limitation to forage/livestock production. The atmosphere consists of about 80 percent N. However, the N in the atmosphere is in the form of an inert gas that is unavailable to plants. Nature provides some N production from sources such as soil bacteria, blue-green algae, and atmospheric lightning. Most commercially available N is synthetically made using the Haber-Bosch process which combines atmospheric N with hydrogen gas under high pressure and temperature to produce ammonium nitrate and urea. Legume plants also have the ability to produce substantial quantities of low-cost N.

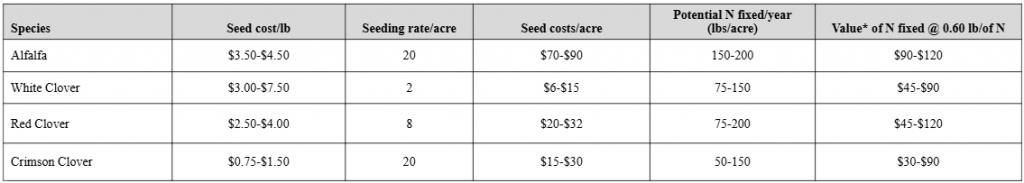

Most legumes have a symbiotic or mutually beneficial relationship with Rhizobium type bacteria. The bacteria infect the roots of legumes from which they obtain food, and the bacteria obtain N from the soil air and fix it into a form usable by plants. This fixed N is accumulated in small appendages called nodules that form on the roots of the legume plant. This allows them to provide enough N for their own growth as well as some or all of the N needed for associated plants growing in the same field. Most fixed N is found in leaves and stems. In a pasture, this fixed N is primarily available as protein and is consumed by grazing livestock. Much of the N consumed as forage is recycled through urine and manure. As roots, stems, and leaves decay over time, N is released for use by other plants. In numerous studies, the amount of N produced per acre by a good stand of alfalfa or clover ranges from 50 to 200 pounds per acre (Table 1). With N at $0.60 pound (urea at $555 per ton) this would be equivalent to $30 to $120 per acre.

Table 1. Seed cost, seeding rate, potential nitrogen fixed, and value of the fixed nitrogen produced by common legume species.

The range of N fixation potential for the legume species listed in Table 1 is wide and partially related to the percentage of legumes growing in the grass stand. The lower end of the range in Table 1 would represent the amount of N fixed when about 30% of the stand consists of legumes, whereas the upper end would reflect pure stands of legumes under ideal growing conditions. Legume plants should be well distributed across the pasture to see a more uniform response and it is recommended that legumes make up at least 30% of the pasture for no additional N to be applied to the system. Over time, consistent use of legumes in grass pastures will help build soil quality, increase plant diversity, boost productivity, improve forage quality and help extend the grazing system.