USDA’s January World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) held big surprises with increases in U.S. production from the 2023-24 crop year. Comparatively the February WASDE, released on Feb. 8, is quite boring. For corn and soybeans, the most relevant changes come from Brazilian production and U.S. demand estimates.

South American Corn & Soy Production

There has been much speculation about the Brazilian corn and soybean crop this year, with a keen focus on drought and high temperature’s impacts on production. USDA’s estimates remain high for both crops as compared to private estimates, with a decline of only 1 million metric tons (MMT, -0.6%) in soybeans and 3 MMT in corn (-2.4%) compared to the January WASDE. The corn reduction is in line with industry expectations, and the soybean reduction is slightly smaller than pre-report industry estimates. Somewhat surprisingly, USDA’s estimates for the 2022/23 Brazilian soybean crop had a larger change than the 2023/24 crop, increasing 2 MMT (+1.3%) from previous estimates.

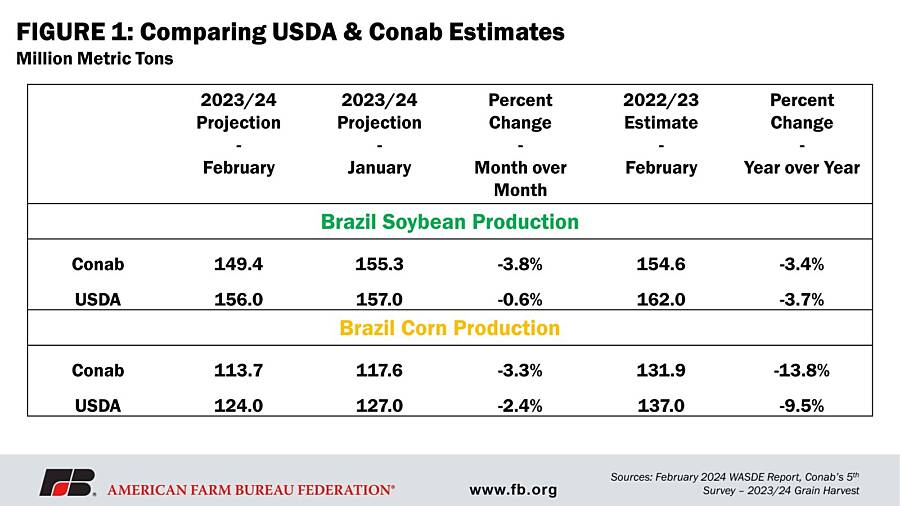

Conab, Brazil’s government entity that publishes production forecasts, also published new estimates only a few hours before USDA (Figure 1). While both countries estimated declines in Brazilian soy and corn production, Conab dropped their monthly forecast further on a percentage basis for both corn and soybeans. Conab also estimates a larger percentage decrease in corn year-over-year estimates, and a similar percentage decrease in soybean year-over-year estimates. USDA consistently projects or estimates larger Brazilian corn and soybean crops than Conab.

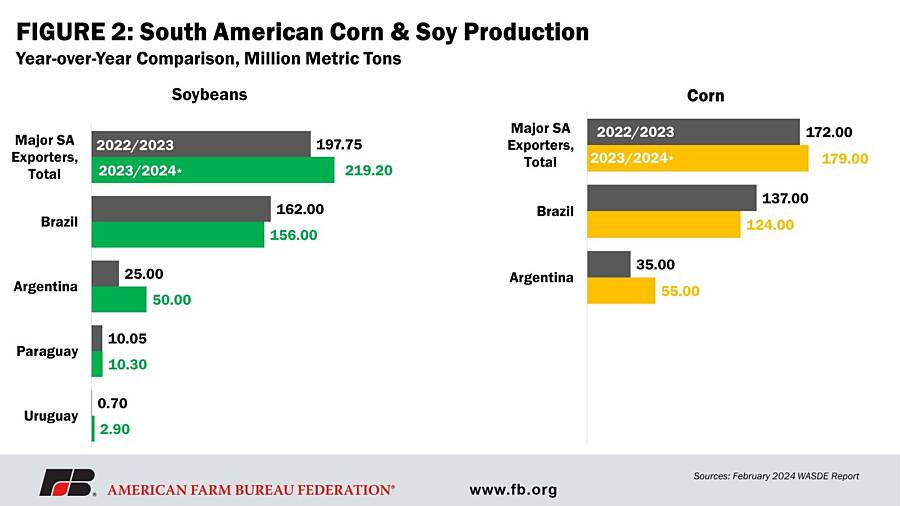

Looking beyond Brazil, the only changes in South American production was a 1 MMT increase (+2.9%) in Argentina’s 2022/23 corn crop and a 0.3 MMT increase (+3.1%) in Paraguay’s 2022/23 soybean crop. Despite decreases in Brazil’s production, Argentina’s rebound from a disastrous crop last year will ensure that South American production in major exporting countries increases year-over-year (Figure 2).

The outcome in South America is still dynamic. Brazil is currently harvesting its soybeans, and simultaneously planting its safrinha (second) corn crop, which currently accounts for 75-80% of its annual corn production. Over 7 million acres of soybeans were replanted in Brazil this year, which will potentially eliminate the possibility of planting the safrinha on those acres. Headed into their production season, Argentina was experiencing pristine conditions with plenty of soil moisture. However, an extended dry spell at critical production times cast doubt on whether Argentina will reach what one Argentina government official called a “super harvest.”

Domestic consumption projections for both corn and soybeans were reduced – subsequently increasing ending stocks. For corn, a 10-million-bushel decrease (-0.1%) in food, seed and industrial use was mirrored in a 10-million-bushel increase (+0.5%) in domestic corn ending stocks. The change in soybeans was larger. A 35-million-bushel decrease (-2.0%) in soybean exports, coupled with an offsetting marginal increase in seed and decrease in residual use, led to a 35-million-bushel increase (+12.5%) in domestic soybean ending stocks. This substantial percentage increase in stocks pushes ending stocks above the 300-million-bushel threshold, to 315-million-bushels. The average farm price per bushel decreased by 10 cents to $12.65 (-0.8%).

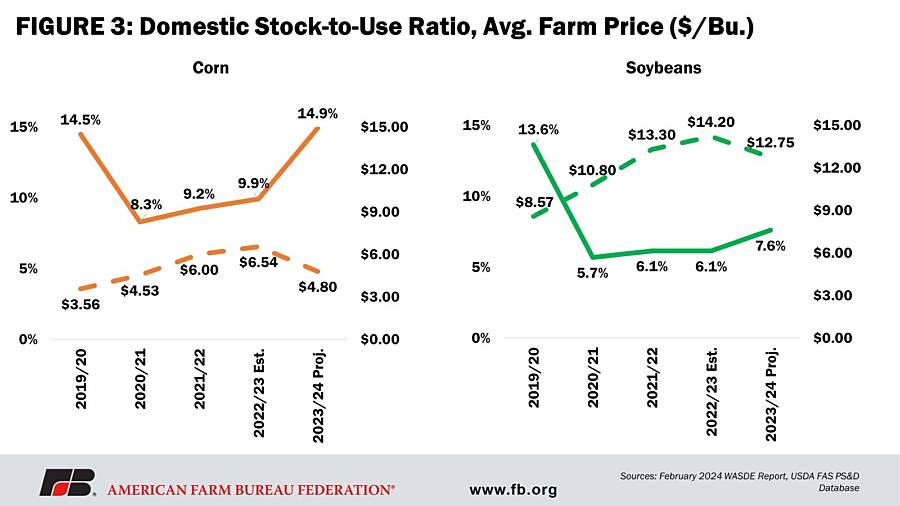

Both corn and soybean stock-to-use ratios edged up in this report, increasing by 0.1 percentage points to 14.9% for corn and 0.9 percentage points to 7.6% for soybeans (Figure 3). The increasing stock-to-use ratio is indicative of a loosening of supply for both corn and soybeans, which is playing out in the market with decreasing prices, with corn and soybean prices at or near three-year lows. The February WASDE report gave no reason for prices to turn around.

Takeaways & Looking Ahead

The February WASDE report continued a bearish trajectory for corn and soybeans. USDA refrained from decreasing Brazilian production significantly, and reduced domestic corn and soybean use. The report overall is more bearish for soybeans than for corn, with an increase in global ending stocks of soybeans and a decrease in global ending stocks of corn.

The market will have to continue to wait and see what production finally comes out of South America. This report will be a quick blip in the news cycle, as a peek into 2024/25 U.S. demand and supply projections will be published next week at the USDA’s 100th Annual Agricultural Outlook Forum in Washington, D.C.

As we start to think about the 2024/25 marketing year, another thing to pay close attention to is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. We are currently in a Super El Niño cycle and are forecast to head into an ENSO-neutral between April and June. Also on Feb. 8, the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña watch, which means we have an over 50% chance of entering into a La Niña cycle this summer. A La Niña cycle typically brings drier conditions to Brazil, Argentina and the U.S., having major impacts on all three countries’ agriculture production.

Story Credit: Betty Resnick, AFBF Market Intel