In recent years, substantial progress has been made in understanding biological and genetic sources of variation in feed efficiency of growing cattle consuming energy-dense, mixed diets during the post-weaning phase. In contrast, much less is known about feed efficiency of cattle consuming moderate- to low-quality forage diets. This is important because approximately 74% of the total feed required to produce beef comes from forage. Indeed, the ruminant animal’s primary advantage over non-ruminant species is its ability to convert forage—essentially sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide—into a high-quality human food source. With increased heifer retention over the next few years, perhaps now is an opportune time to consider strategies for improving forage use efficiency in replacement females.

Forage utilization efficiency has been a major research focus of our group at Oklahoma State University. Although grazing studies are ultimately the goal, we began this line of work in a controlled pen setting where forage intake can be measured accurately. Each year, we evaluate a contemporary group of weaned replacement heifers and a contemporary group of five-year-old cows. The cows are tested during lactation and again during gestation. During each test period, cattle spend approximately 90 days in our forage intake facility (Fig. 1).

Cattle are fed bermudagrass hay and provided mineral with free-choice access to both. The hay typically contains 12 to 14% crude protein and approximately 57 to 60% total digestible nutrients (TDN). High-quality bermudagrass hay was selected so that protein requirements of growing heifers and lactating cows are met without the need for protein supplementation. Importantly, the hay is fed unprocessed (not ground, chopped, or shredded), allowing us to evaluate intake and performance under conditions similar to many real-world forage systems.

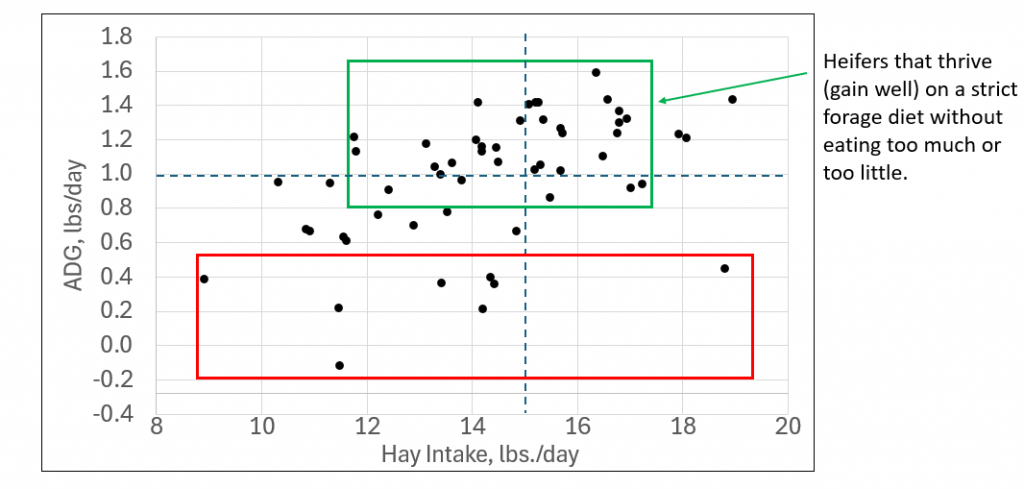

Substantial phenotypic variation is observed within each contemporary group. As an example, forage intake and weight gain for the 2024 weaned replacement heifers are shown in Figure 2. Average daily forage intake ranged from 9 to 19 pounds per day, while average daily gain (ADG) ranged from slight weight loss to gains of 1.6 pounds per day. Notably, heifers with unacceptable weight gain have been observed in every contemporary group, as indicated by the red rectangle in Figure 2. At the same time, many heifers exhibited moderate forage intake coupled with acceptable—or even exceptional—weight gain (green rectangle). Our working hypothesis is that heifers demonstrating moderate forage intake with acceptable growth will ultimately become more forage-efficient cows. Simply put, we define an efficient cow as one that is highly productive without consuming excessive amounts of forage.

In this article, we focus specifically on the forage performance (gain) component of efficiency. Our group, along with several others, has conducted experiments to determine whether cattle that rank high for weight gain when consuming an energy-dense diet (such as a bull-test diet) also rank high for gain when consuming forage. To date, the answer appears to be no. Across seven independent studies, no statistically significant positive correlations have been detected between gain on concentrate-based diets and gain on forage-based diets. In fact, the average correlation across studies is near zero. These results suggest that growth performance on energy-dense diets is largely unrelated to growth performance on moderate-quality forage. Additional research is clearly needed, including larger experiments with sufficient data to estimate genetic correlations.

The encouraging news is that measuring forage-based growth performance is neither difficult nor expensive. Producers need only a reliable scale and a 70- to 100-day period during which heifers are grazing moderate-quality forage (or consuming hay) with little or no supplementation. In practice, some producers may already be selecting for forage performance—perhaps unintentionally. For example, low-input heifer development programs, short breeding seasons, and retaining only heifers that conceive early may naturally favor females that perform and reproduce efficiently on forage-based systems.

Considerable variation exists among heifers in their ability to gain weight on moderate-quality forage, and this variation appears largely independent of performance on energy-dense diets. Simple measurements of forage-based weight gain, or well-designed development programs intended to challenge heifers to perform (with minimal or no concentrate feed), and become pregnant early in the breeding season may help identify heifers that are better suited for efficient, forage-based cow-calf production systems.